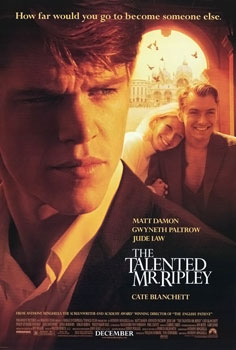

I recently watched two movies within the span of a week I had never seen before. Taken jointly, they articulate the economic anxiety many currently feel in society. They are the psychological thriller The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) and the modern day western Hell or High Water. The movies are critically acclaimed and have strong ensemble casts. I hated Ripley. I loved Hell.

In a three reel comparison, the economic arguments of The Talented Mr. Ripley and Hell or High Water.

***SPOILERS WARNING***

The Talented Mr. Ripley: All major plot points.

Hell or High Water: General movie thesis. Fewer plot points than a movie review.

First Reel: The Talented Mr. Ripley

The Talented Mr. Ripley based on the 1955 novel of the same name by Patricia Highsmith tells the story of Tom Ripley, a young man low on the economic totem pole who finds himself through luck, imitation, and lying rubbing elbows with the heir to a shipbuilding empire (Dickie Greenleaf), his female partner, their cocky womanizing friend, an heiress (Meredith), and a closeted gay socialite (Peter). The Talented Mr. Ripley is equal parts drama and thriller with Ripley at the core.

The Talented Mr. Ripley based on the 1955 novel of the same name by Patricia Highsmith tells the story of Tom Ripley, a young man low on the economic totem pole who finds himself through luck, imitation, and lying rubbing elbows with the heir to a shipbuilding empire (Dickie Greenleaf), his female partner, their cocky womanizing friend, an heiress (Meredith), and a closeted gay socialite (Peter). The Talented Mr. Ripley is equal parts drama and thriller with Ripley at the core.

Ripley is approached with a job offer shortly after the opening credits. I immediately felt anxiety over the request and the duplicity of accepting it. As Ripley arrives in Italy and befriends Meredith through bald-faced lying my anxiety increased. At no point in this film did I feel comfortable, and my anxiety was never thriller induced excitement.

Simply, Ripley is a horror film for the one percent. A talented nobody who believes “it would be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody” successfully ingratiates himself to industrious old money (shipping) through the subterfuge of pretending to be a friend of the family’s heir and promising to convince the prodigal son to return home. Once there, he proceeds to get in with the son by guile and parlor tricks of impersonation, thus enabling the son to waste more of the family fortune before murdering the son when scorned. This lowborn imposter then proceeds to take the identity of the son and live a consumption filled double life. [He] then murders the intelligent friend who discovers his ruse, evades capture by the authorities through the (unwitting) help of a potential gay lover, and gaslights the son’s distraught partner. Justice is finally served when the upstart living above his station decides to murder his gay lover to preserve his secrets, thus denying the “talented” Mr. Ripley the happiness and individual validation he so desperately seeks.

There is a homophobic undertone to the whole movie. Ripley is heavily implied to be in love with Dickie (see the shot of Ripley sleeping in the boat with Dickie corpse) yet also wants to BE Dickie, impersonating and replicating Dickie’s life. Ripley’s closeted gay companion Peter aids Ripley’s duping of the Italian police, but does so unknowingly through Ripley’s guile and is ultimately killed by Ripley. So to keep score of the movie’s theories: homosexuals secretly want to be their social betters, homosexuals use their homosexual friends to avoid punishment, and homosexuals deserve the brutal justice of murdering their lovers.

This is what passed for excellent entertainment at the dawn of the new millennium.

Second Reel: Hell or High Water

Hell or High Water is the story of two brothers – Tanner and Toby Howard – who rob banks for the money to avoid foreclosure on the family farm in west Texas. Two Texas Rangers – one a week from retirement, the other a Native American in the prime of life – are on the hunt for them. Hell or High Water is a modern western, one that uses its setting to show how the environment shapes people.

Hell or High Water is the story of two brothers – Tanner and Toby Howard – who rob banks for the money to avoid foreclosure on the family farm in west Texas. Two Texas Rangers – one a week from retirement, the other a Native American in the prime of life – are on the hunt for them. Hell or High Water is a modern western, one that uses its setting to show how the environment shapes people.

The hell that is West Texas is one ravaged by economic boom and bust: for those with means – the banks – oil fields are automated money mints and the displaced workers who are no longer needed to work the fields are targets for foreclosure on failure to pay their debts. The small towns are blighted but the people still eek by, fiercely willing to defend what’s theirs though disobedience and personal firearms. Movie westerns are typically set in the 1800’s to give a reason for outlaw and deputized justice and to allow the plausibility such a sparse population are all crack shots with a long barrel rifle. Hell or High Water needs no pretense. West Texans only own what they know how to use.

Infinitely quotable, every character from top billing to “T-Bone Waitress” has a Texas sized personality. As the brothers hold up one bank, a teller and an impossibly old man, the old man calmly informs the brothers he has a gun saying, “You’re damn right I got a gun on me. Y’all going to steal my gun too?” They don’t. They only steal from banks. The common populous’ responses to the main characters were believable and appreciated: some tried to stop the bank robberies; others were difficult with the police, their questions, and the demands of the law; all openly hated the banks. You are not made to like these characters; you are made to know them.

Hell or High Water does not hide the impossibility of its tale. For those without means there are two choices: facing Hell or facing High Water. No character remains unscathed. None expect a reprieve. Right before the third act kicks in, Toby visits his son, potentially for the last time. Their sparse exchange encapsulates the movie’s thesis:

Toby: “You may be hearing a lot of things about me and your uncle.”

Justin: “Whatever I hear I won’t believe.”

Toby: “No, you believe it, I did all of it.”

Third Reel: Opposite Sides of an Oppressive Coin

Despite their disparate subject matter, the two movies are connected from opposite poles by the same economic worldview. Money is power’s tangible object. The rich have it and are weary of losing it whilst they present their wealth; everyone else wants to be rich for the real (economic security) or imagined (identity) benefits. The talented poor can better their situations but only through guile and murder while paying a price for their betterment in the end. Justice always comes to those who try and do something about injustice.

Both movies focus more on character than plotting, though whether you prefer slipping in the heads of laissez-faire wealth or the skins of tempered grit will be a personal preference. Though the writing, casting, acting, and directing of the two films is top notch, I prefer the scrappy, prideful downtrodden to the nouveau riche. There are few instances where I hate a movie with a pedigree of Damon, Law, Paltrow, Seymour Hoffman, and Blanchett (Mystic River is one, Tarantino films are another), but Ripley is hollow and remains hollow. Hell does not hide its determinism.

As the final reel wraps up in both, economics dominates. Maybe at the height of the tech boom in 1999 I would have enjoyed watching over two hours of trust fund babies ruin people’s lives, be cruel to each other, and live in despair. Movies are escapism after all. I find it fitting the novel was written in the post-war economic boom of 1950. But in 2017, during the greatest economic inequality since the Gilded Age where the White House Cabinet has more wealth than a third of Americans The Talented Mr. Ripley gives me hives. I would much rather watch an unadorned, white hat-black hat Western where the escapism matches the times. The Pine, Foster, and Bridges led story of theft from the greedy is real in a way that makes you want to face the world.

Come Hell or High Water.